In an earlier blog post on energy storage I stated that there are two developments related to the widespread use of renewable energy that ‘I would fall on my sword for’, energy storage and smart grids. This post discusses the second of these in the context of large-scale smart grids and smaller minigrids. Both are critical to the future of renewable energy in both developed and developing countries.

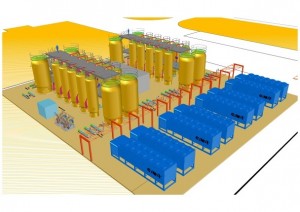

Grids are collections of wires,switches,transformers,substations, and related equipment that enables the delivery of electrical energy from a generator to a consumer of that energy. A traditional grid structure today is shown below:

The first grid, for delivery of alternating current (AC) electricity, was put into operation in 1886. Electrical energy can be delivered as either AC or DC (direct current) electricity, but for over a century AC has been the preferred delivery mechanism. A more complete discussion of AC vs. DC is a good topic for a future blog post.

The traditional grid is a one-way distribution network that delivers power from large centralized generating stations to customers via a radial network of wires. Regional grids, when integrated, constitute a national grid, something the historically balkanized U.S. electric utility system is still trying to achieve. Transmission lines are long distance carriers of electrical energy transmitted at high voltages and low currents to minimize electrical losses due to heating in wires. This high voltage energy is then reduced via transformers to lower voltage, usually 120 or 240 volts, to supply local distribution networks that bring the energy to our homes and businesses. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that national electricity transmission and distribution (T&D) losses average about 6% of the electricity that is transmitted and distributed in the United States each year.

While the traditional grid has brought the benefits of electricity to billions of people for many decades, its shortcomings have become more visible in recent years. The problem is its vulnerability to disruption by extreme weather events (only a small fraction of T&D wires are underground), physical attack and accidents leading to widespread power outages, cyber attack in today’s world of increasing dependence on information technologies, and even large solar storms that strike the earth occasionally and interact with the T&D system acting as giant antennas.

The utility industry has usually (but not always) resisted putting wires underground because of high costs, and increased effort is going into trimming trees that can fall on or otherwise disrupt power lines. Control of the grid has also been improved to minimize the possibility of disruption in one grid sector spreading to others, but this is a costly work in progress. What is looming as a major threat to the traditional grid is its increasing dependence on automated remote control via advanced computer/information technologies built into the grid system that are vulnerable to hacking and other malevolent interventions.

Grid systems with computer controls are referred to as smart grids. Through the gathering, communication, analysis, and application of analog or digital information on the behavior of suppliers and consumers, a smart grid can use automation “..to improve the efficiency, reliability, economics, and sustainability of the production and distribution of electricity.” The issue of cyber vulnerability has only begun to receive careful attention in recent years as the hacking phenomenon has surged and the ability to interrupt remote industrial activities via computer viruses such as Stuxnet have been demonstrated.

What can be done to protect against this vulnerability? Considerable effort is going into developing software that is resistant to hacking, but this is proving extremely difficult to achieve. As has become all too obvious, there are lots of talented hackers out there and some of them are supported by national governments. Nevertheless, this is a path that has to be pursued, and is becoming a priority in the training of new IT programmers and specialists.

Another approach is to move away from the historic centralized grid and move to a grid system where disturbances can be isolated (islanded) once detected and thus unable to affect other parts of the grid. This will require distributed generation sources that supply unaffected parts of the grid, and could be other centralized generators that can be tapped or local renewable energy sources (wind, solar) that are not in the disturbed grid sector.

Traditional grids are expensive, and extending these grids from urban to remote areas often can not be justified economically. This is particularly true in developing countries where most of the world’s 1.5 billion people without access to electricity reside. Improving access to modern energy services in rural areas is a major development priority, and there is increasing attention to decentralized generation and distribution through mini-grids. “A ‘mini-grid’ is an isolated, low-voltage distribution grid, providing electricity to a community – typically a village or very small town. It is normally supplied by one source of electricity, e.g. diesel generators, a solar PV installation, a micro-hydro station, etc., or a combination of the above.” It includes control capability, which means it can disconnect from a traditional grid and operate autonomously.

A recent workshop organized by the Africa-EU Renewable Energy Cooperation Programme (RECP), held in Tanzania in September 2013, focused on this rapidly emerging option – ‘Mini-Grids: Opportunities for Rural development in Africa’. The workshop background was described as follows: “Given Africa’s abundance of renewable energy resources, the widespread existence of isolated, expensive, highly-subsidized fossil-fuel based mini-grids on the continent, very low grid connection rates, the often low levels of electricity demand from households, the high costs associated with grid extension, the lack of reliable, centralized generation capacity and increasing levels of densification as a result of ongoing urbanization, renewable energy and hybrid-based mini-grids provide a practical, efficient energy access solution.” It should also be noted that the use of renewables can reduce fossil-fuel use, reduce carbon emissions, and create local jobs and economic development.

Another type of mini-grid is the micro-grid, a term used to describe mini-grids that deliver DC electricity to its consumers. Still another variation is the skinny-grid, which emphasizes the use of energy efficiency technologies to reduce consumer demand and thus allow the use of thinner and less expensive connecting wires between generators and end users.

I will conclude this blog post by discussing the role of smart grids in facilitating the integration of renewable energy into the grid. Renewable energy is now growing rapidly as a share of the global energy mix and this trend will continue as we move further into the 21st century. We are also learning that, despite the variable nature of solar and wind energy, by using the control features of increasingly sophisticated smart grids and the use of energy storage, this integration can be done safely and cost effectively with high levels of renewables penetration.

IRENA, the International Renewable Energy Agency headquartered in Abu Dhabi, has addressed this issue in a comprehensive November 2013 report entitled ‘Smart Grids and Renewables’. As stated in the Executive Summary: “This report is intended as a pragmatic user’s guide on how to make optimal use of smart grid technologies for the integration of renewables into the grid. …The report also provides a detailed review of smart grid technologies for renewables, including their costs, technical status, applicability and market maturity for various uses.” It acknowledges that “Much of what is known or discussed about smart grids and renewables in the literature is still at the conceptual/visionary stage..” but includes “..several case studies that involve actual, real-world installation and use of smart-grid technologies that enable renewables.” The report also points to needed policy and regulatory changes for successful renewables integration. It is a valuable and forward-looking document.