History has always been my favorite subject, starting in high school, and still constitutes a major part of my personal reading. Needless to say I have a strong interest in other topics as well, as attested to by my long career in science and engineering and education/mentoring activities with young people. What often fascinates me is looking back at how things have changed in the past, often in unexpected ways, and how people looking back in the decades ahead will put their perspectives on what we are doing today. This blog post is my attempt to flesh out these thoughts, while acknowledging the difficulty of looking into the future. If I look far enough into that future I will not be around to suffer the slings and arrows of projecting incorrectly, or collecting the kudos for projecting accurately. Nevertheless, it feels like a stimulating and challenging activity to undertake, and so here goes.

Let me start by going back seven decades to the 1940s when I was a young kid growing up in the Bronx and just beginning to form my likes and dislikes and develop opinions. My love for science fiction developed at that time and was probably a dead give-away of my future career interests. An important shaping event was the dropping of the first atomic bomb on Japan on August 6, 1945, an event that I still clearly remember learning about on the radio while sitting in the back seat of my parents’ car. Without a deep or much of any understanding at that time, I somehow sensed that the world had changed in that August moment. I still feel that way after many subsequent years of reading and studying.

The following decades saw several other unexpected and defining events: the addition of fusion weapons (hydrogen bombs) to our nuclear arsenals, commercial applications of controlled nuclear fission (nuclear submarines and nuclear-powered surface ships, and the first commercial nuclear power plant which was actually a land-based nuclear submarine power plant), development and emergence of the transistor as a replacement for vacuum tubes (first using germanium and then silicon), the development of the first solar cell at Bell Labs, the development and application of laser technology, the emergence of the information technology industry based on the heretofore abstract concepts of Boolean algebra (0s and 1s), and the increasing attention to a wide range of clean energy technologies that had previously been considered impractical for wide scale application – wind, solar, geothermal, ocean energy, fuel cells, advanced battery technologies, and a broad range of alternative liquid and gaseous fuels. Each in its own way has already changed and will further change the world in future decades, as will other technologies that we now only speculate about or cannot imagine. This is the lesson of history – it is difficult for most of us to look ahead and successfully imagine the future, and one of my earlier blog posts (‘Anticipating the Future: It Can Be Difficult’) discusses this topic. In the following paragraphs I speculate about the future with humility but also great anticipation. My only regret is that I will not live long enough to see most of this future unfold.

I will divide this discussion into two parts on which I have focused some attention and feel that I have some knowledge – medicine/health care, and energy. That leaves all too many aspects of the future that I don’t feel qualified to comment upon – e.g., what more will we learn about Amelia Earhart’s disappearance, Cuba’s possible participation in John Kennedy’s assassination, and the future of the tumultuous Middle East and the countries of the former Soviet Union. My primary focus in this post will be on the latter of the two parts, energy.

To help you understand my interest in medicine and health care I confess that at one point in my career, before committing to pursuing a PhD in physics, I gave serious consideration to attending medical school. During this period in the early 1960s I was a research scientist at Texas Instruments (TI) and was excited about the possibilities of miniature electronics which TI was pioneering in. I even suggested to my TI bosses that we undertake the application of transistors and sensors to artificial vision, but it was much too early for the company to make such a commitment. Today, 50 years later, that vision is being realized.

I also see great promise in the application of miniature electronics to continuous in-vivo diagnosis of human health via capsules that float throughout a human’s blood network, monitor various chemical components, and broadcast the results to external receivers. This will depend on low-powered miniature sensors and analysis/broadcast capability powered by long-lasting miniature batteries or an electrical system powered by the human body itself. Early versions are now being developed and I see no long-term barriers to developing such a system.

A third area in which I see great promise is the non-invasive monitoring of brain activity. This is a research area that I see opening up in the 21st century as we are beginning to have the sensitive tools necessary to explore the brain in detail. Given that the brain is responsible for so many aspects of our mental and physical health I expect great strides in the coming decades in using brain monitoring to address these issues.

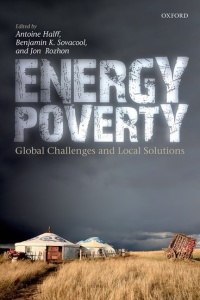

The energy area is where I have devoted the bulk of my professional career and where my credibility may be highest – at least I’d like to think so. Previous blog posts address my thoughts on a wide range of current energy, water-energy, and related policy issues. Recognizing that changes in our energy systems come slowly over decades and sometimes unexpectedly, as history tells us, I will share my current thoughts on where I anticipate we will be in 30-40 years.

Let me start with renewable energy – i.e., solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal, biomass, and ocean energy. I have commented on each of these previously, but not from a 30-40 year perspective. Renewables are not new but, except for hydropower, their entering or beginning to enter the energy mainstream is a relatively recent phenomenon. Solar in the form of photovoltaics (PV) is a truly transformative technology and today is the fastest growing energy source in the world, even more so than wind. This is due to significant cost reductions for solar panels in recent years, PV’s suitability for distributed generation, its ease and quickness of installation, and its easy scalability. As soon as PV balance-of-system costs (labor, support structures, permitting, wiring) come down from current levels and approach PV cell costs of about $0.5-0.7 per peak watt I expect this technology to be widespread on all continents and in all developed and developing countries. Germany, not a very sunny country but the country with the most PV installed to date, has even had occasional summer days when half its electricity was supplied by solar. In combination with energy storage to address its variability, I see PV powering a major revolution in the electric utility sector as utilities recognize that their current business models are becoming outdated. This is already happening in Germany where electric utilities are now moving rapidly into the solar business. In terms of the future, I would not be surprised if solar PV is built into all new residential and commercial buildings within a few decades, backed up by battery or flywheel storage (or even hydrogen for use in fuel cells as the ultimate storage medium). Most buildings will still be connected to the grid as a backup, but a significant fraction of domestic electricity (30-40%) could be solar-derived by 2050. The viability of this projection is supported by the NREL June 2012 study entitled ‘Renewable Electricity Futures Study’.

Hydropower already contributes about 10% of U.S. electricity and I anticipate will grow somewhat in future decades as more low-head hydro sites are developed.

For many years onshore wind was the fastest growing renewable electricity source until overtaken recently by PV. It is still growing rapidly and will be enhanced by offshore wind which currently is growing slowly. However, I expect offshore wind to grow rapidly as we approach mid-century as costs are reduced for two primary reasons: it taps into an incredibly large energy resource off the coasts of many countries, and it is in close proximity to coastal cities where much of the world’s population is increasingly concentrated. In my opinion, wind, together with solar and hydro, will contribute 50-60% of U.S. electricity in 2050.

Other renewable electric technologies will contribute as well, but in smaller amounts. Hot dry rock geothermal wells (now called enhanced geothermal systems) will compete with and perhaps come to dominate traditional geothermal generation, but this will take time. Wave and tidal energy will be developed and become more cost effective in specific geographical locations, with the potential to contribute more in the latter part of the century. This is especially true of wave energy which taps into a large and nearly continuous energy source.

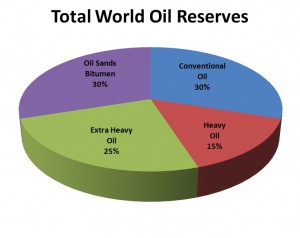

Biomass in the form of wood is an old renewable energy source, but in modern times biomass gasification and conversion to alternative liquid fuels is opening up new vistas for widescale use of biomass as costs come down. By mid-century I expect electrification and biomass-based fuels to replace our current heavy dependence on petroleum-based fuels for transportation. This trend is already underway and may be nearly complete in the U.S. by 2050. Biomass-based chemical feedstocks will also be widely used, signifying the beginning of the end of the petroleum era.

I expect that other fossil fuels, coal and natural gas, will still be used widely in the next few decades, given large global resources. Natural gas, as a cleaner burning fossil fuel, and with the availability of large amounts via fracking, will gradually replace coal in power plants and could represent 30-40% of U.S. power generation by mid-century with coal generation disappearing.

To this point I have not discussed nuclear power, which today provides close to 20% of U.S. electricity. While I believe that safe nuclear power plants can be built today –i.e., no meltdowns – cost, permanent waste storage, and weapons proliferation concerns are all slowing nuclear’s progress in the U.S. Given the availability of relatively low-cost natural gas for at least several decades (I believe fracking will be with us for a while), the anticipated rapid growth of renewable electricity, and the risks of nuclear power, I see limited enthusiasm for its growth in the decades ahead. In fact I would not be surprised to see nuclear power supplying only about 10% of U.S. electricity by 2050, and less in the future.

To summarize, my picture today of an increased amount of U.S. electricity generation in 2050 is as follows:

Generating Technology : Percent of U.S. Generation in 2050

nuclear: 5-10

coal: 0-5

Oil: 0

natural gas: 30-40

solar + wind + hydro: 50-60

other renewables: 5-10

I am sure that some readers of this post will take strong issue with my projections and have very different thoughts about the future. I welcome their thoughts and invite them to join me in looking ahead. As the title of this post acknowledges, looking ahead is risky business, but it is something I’ve wanted to do for a while. This seems as good a time as any to do so.