Buildings account for approximately 40 percent of the energy (electrical, thermal) used in the U.S. and Europe, and an increasing share of energy used in other parts of the world. Most of this energy today is fossil-fuel based. As a result, this energy use also accounts for a significant share of global emissions of carbon dioxide.

Source: U.S. Department of Energy, Buildings Energy Data Book

These simple facts make it imperative that buildings, along with transportation fleets and power generation, be primary targets of reduced global energy and fossil fuel demand. This blog post discusses one approach in buildings that is gaining increasing visibility and viability, the introduction of net zero energy buildings and the retrofit of existing buildings to approach net zero energy operation. A net zero energy building (NZEB or ZEB) is most often defined as a building that, over the course of a year, uses as much energy as is produced by renewable energy sources on the building site. This is the definition I will focus on. Other ZEB definitions take into account source energy losses in generation and transmission, emissions (aka zero carbon buildings), total cost (cost of purchased energy is offset by income from sales of electricity generated on-site to the grid), and off-site ZEB’s where the offsetting renewable energy is delivered to the building from off-site generating facilities. Details on these other definitions can be found in the 2006 NREL report CP-550-39833 entitled “Zero Energy Buildings: A Critical Look at the Definition”.

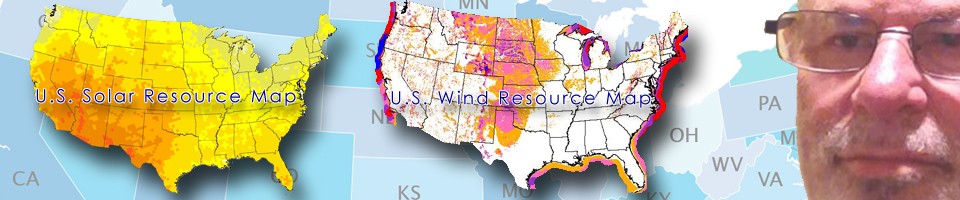

The keys to achieving net zero energy buildings are straight forward in principle: first focus on reducing the building’s energy demand through energy efficiency, and then focus on meeting this energy demand, on an annual basis, with onsite renewable energy – e.g., use of localized solar and wind energy generation. This allows for a wide range of approaches due to the many options now available for improved energy efficiency in buildings and the rapidly growing use of solar photovoltaics on building roofs, covered parking areas, and nearby open areas. Most ZEB’s use the electrical grid for energy storage, but some are grid-independent and use on-site battery or other storage (e.g., heat and coolth).

A primary example of what can be done to achieve ZEB status is NREL’s operational RSF (Research Support Facility) at its campus in Golden, Colorado, shown below.

It incorporates demand reduction features that are widely applicable to many other new buildings, and some that make sense for residential buildings and retrofits as well (cost issues are discussed below). These include:

– optimal building orientation and office layout, to maximize heat capture from the sun in winter, solar PV generation throughout the year, and use of natural daylight when available

– high performance electrical lighting

– continuous insulation precast wall panels with thermal mass

– windows that can be opened for natural ventilation

– radiant heating and cooling

– outdoor air preheating, using waste heat recovery, transpired solar collectors, and crawl space thermal storage

– aggressive control of plug loads from appliances and other building equipment

– advanced data center efficiency measures

– roof top and parking lot PV arrays

U.S. ZEB research is supported by DOE’s Building America Program, a joint effort with NREL, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and several industry-based consortia – e.g., the National Institute of Building Sciences and the American Institute of Architects. Many other countries are exploring ZEB’s as well, including jointly through the International Energy Agency’s “Towards Net Zero Energy Solar Buildings” Implementing Agreement (Solar Heating and Cooling Program/Task 40). This IEA program has now documented and analyzed more than 300 net zero energy and energy-plus buildings worldwide (an energy-plus building generates more energy than it consumes).

An interesting example of ZEB technology applied to a residential home is NREL’s Habitat for Humanity zero energy home (ZEH), a 1,280 square foot, 3-bedroom Denver area home built for low income occupants. NREL report TP-550-431888 details the design of the home and includes performance data from its first two years of operation (“The NREL/Habitat for Humanity Zero Energy Home: a Cold Climate Case Study for Affordable Zero Energy Homes”). The home exceeded its goal of zero net source energy and was a net energy producer for these two years (24% more in year one and 12% more in year two). The report concluded that “Efficient, affordable ZEH’s can be built with standard construction techniques and off-the-shelf equipment.”

The legislative environment for ZEB’s is interesting as well. To quote from the Whole Building Design Guide of the National Institute of Building Sciences:

“Federal Net Zero Energy Building Goals

Executive Order 13514, signed in October 2009, requires all new Federal buildings that are entering the planning process in 2020 or thereafter be “designed to achieve zero-net-energy by 2030”. “In addition, the Executive Order requires at least 15% of existing buildings (over 5,000 gross square feet) meet the Guiding Principles for Federal Leadership in High Performance and Sustainable Buildings by 2015, with annual progress towards 100% conformance”.

Two milestones for NZEB have also been defined by the Department of Energy (DOE) for residential and commercial buildings. The priority is to create systems integration solutions that will enable:

Marketable Net Zero Energy Homes by the year 2020

Commercial Net Zero Energy Buildings at low incremental cost by the year 2025.

These objectives align with the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA), which calls for a 100% reduction in fossil-fuel energy use (relative to 2003 levels) for new Federal buildings and major renovations by 2030.”

A word about cost: ZEB’s cost more today to build than traditional office buildings and homes, but not much more (perhaps 20% for new construction). Of course, part of this extra cost is recovered via reduced energy bills. In the future, the zero energy building goal will become more practical as the costs of renewable energy technologies decrease (e.g., PV panel costs have decreased significantly in recent years) and the costs of traditional fossil fuels increase. The recent surge in availability of relatively low cost shale gas from fracking wells will slow this evolution but it will eventually occur. Additional research on cost-effective efficiency options is also required.

To sum up, the net zero energy building concept is receiving increasing global attention and should be a realistic, affordable option within a few decades, and perhaps sooner. ZEB’s offer many advantages, as listed by Wikipedia:

“- isolation for building owners from future energy price increases

– increased comfort due to more-uniform interior temperatures

– reduced total net monthly cost of living

– improved reliability – photovoltaic systems have 25-year warranties – seldom fail during weather problems

– extra cost is minimized for new construction compared to an afterthought retrofit

– higher resale value as potential owners demand more ZEBs than available supply

– the value of a ZEB building relative to similar conventional building should increase every time energy costs increase

– future legislative restrictions, and carbon emission taxes/penalties may force expensive retrofits to inefficient buildings”

ZEB’s also have their risk factors and disadvantages:

“- initial costs can be higher – effort required to understand, apply, and qualify for ZEB subsidies

– very few designers or builders today have the necessary skills or experience to build ZEBs

– possible declines in future utility company renewable energy costs may lessen the value of capital invested in energy efficiency

– new photovoltaic solar cells equipment technology price has been falling at roughly 17% per year – It will lessen the value of capital invested in a solar electric generating system. Current subsidies will be phased out as photovoltaic mass production lowers future price

– challenge to recover higher initial costs on resale of building – appraisers are uninformed – their models do not consider energy

– while the individual house may use an average of net zero energy over a year, it may demand energy at the time when peak demand for the grid occurs. In such a case, the capacity of the grid must still provide electricity to all loads. Therefore, a ZEB may not reduce the required power plant capacity.

– without an optimised thermal envelope the embodied energy, heating and cooling energy and resource usage is higher than needed. ZEB by definition do not mandate a minimum heating and cooling performance level thus allowing oversized renewable energy systems to fill the energy gap.

– solar energy capture using the house envelope only works in locations unobstructed from the South. The solar energy capture cannot be optimized in South (for northern hemisphere, or North for southern Hemisphere) facing shade or wooded surroundings.”

Finally, it is important to note that the energy consumption in an office building or home is not strictly a function of technology – it also reflects the behavior of the occupants. In one example two families on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts lived in identical zero-energy-designed homes and one family used half as much electricity in a year as the other. In the latter case electricity for lighting and plug loads accounted for about half of total energy use. As energy consultant Andy Shapiro noted: “There are no zero-energy houses, only zero-energy families.”