The article by Dr. Maria Zuber that is reproduced below, and appeared recently in the Washington Post, is a thoughtful, intelligent, and realistic approach to addressing coal issues in the United State. It recognizes the realities of our evolving energy system as renewable energy begins to displace energy from fossil fuels, but also recognizes that some people will be adversely impacted as this transition unfolds. As a compassionate nation we must take these impacts into account as we move forward to a clean energy future. Dr. Zuber’s careful thoughts on this issue are well worth reading.

……………………………

How to declare war on coal’s emissions without declaring war on coal communities

By Maria T. Zuber February 24, 2017

Maria T. Zuber is the vice president for research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Chair of the National Science Board.

I grew up in a place named for coal: Carbon County, Pa., where energy-rich anthracite coal was discovered in the late 1700s. By the early 1900s, eastern Pennsylvania employed more than 180,000 miners. By the 1970s — when I left Carbon County for college — just 2,000 of those jobs remained.

For decades, my family’s path traced the arc of the industry. Both my grandfathers mined anthracite. My father’s father died of black lung before I was born. My mother’s father lived long enough to get a pink slip, teach himself to repair TVs and radios and finally get a job on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. He often slept in a recliner because he couldn’t breathe in bed. He had black lung, too.

We faced economic challenges, but thanks to my father’s career as a state trooper, we had more security than most. Still, our neighbors’ struggles left a deep impression on me. When I hear coal-mining communities talk bitterly about a “war on coal,” I understand why they feel under attack. I know the deep anxiety born from years of watching their towns empty out and opportunity evaporate.

I was one of the people who left, in my case to pursue my passion for science. I was lucky: I became the first woman to head a science department at MIT, as well as the first woman to lead a NASA planetary mission.

As a daughter of coal country, I know the suffering of people whose fates are tied to the price of a ton of coal. But as a scientist, I know that we cannot repeal the laws of physics: When coal burns, it emits more carbon dioxide than any other fossil fuel. And if we keep emitting this gas into the atmosphere, Earth will continue to heat up, imposing devastating risks on current and future generations. There is no escaping these facts, just as there is no escaping gravity if you step off a ledge.

The move to clean energy is imperative. In the long run, that transition will create more jobs than it destroys. But that is no comfort to families whose livelihoods and communities have collapsed along with the demand for coal. We owe something to the people who do the kind of dangerous and difficult work my grandfathers did so that we can power our modern economy.

Fortunately, there are ways we can declare war on coal’s carbon emissions without declaring war on coal communities.

First, we should aggressively pursue carbon capture and storage technology, which catches carbon dioxide from coal power plants before it is released into the atmosphere and stores it underground. To be practical, advances in capture efficiency must be coupled with dramatic decreases in deployment costs and an understanding of the environmental impacts of storage. These are not intractable problems; scientific and technological innovations could change the game.

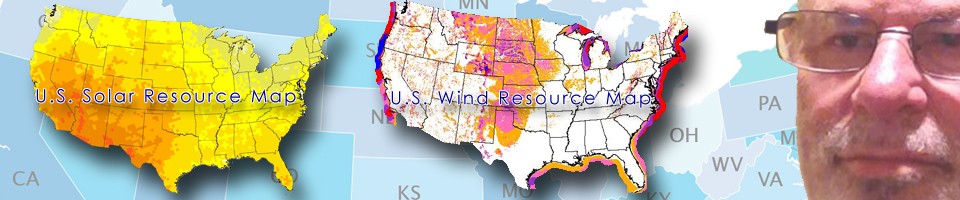

Next, we should look beyond combustion and steel production to find new ways to make coal useful. In 2015, 91 percent of coal use was for electrical power. But researchers are exploring whether coal can be used more widely as a material for the production of carbon fiber, batteries and electronics — indeed, even solar panels.

These avenues hold promise, but even if carbon capture becomes practicable and we expand other uses for coal, the industry will never come roaring back. Globally, coal’s market share is dropping, driven by a range of factors, including cheap natural gas and the rapidly declining costs of wind and solar energy.

That’s why we must also commit to helping the workers and communities that are hurt when coal mines and coal plants reduce their operations or shut down. Policymakers, researchers and advocates have proposed a range of solutions at the federal and state levels to promote economic development; help coal workers transition to jobs in other industries, including renewable energy; and maintain benefits for retired coal workers.

Helping coal country is an issue with bipartisan support. Still, to succeed, strategies such as these may require a champion who, like President Trump, has widespread support in coal country and can address skepticism from coal communities.

Eventually, the practice of burning coal and other fossil fuels for energy — especially without the use of carbon capture and storage technologies — will end. It has to. The question is whether we have the wisdom to end it in an orderly way that addresses the pain of coal communities — and quickly enough to prevent the worst impacts of climate change. Our choices will determine the future not just for coal country, but for all of us.